Jesuit-Enslaved People – Who They Were and Why Their Stories Matter

The history of Jesuit enslavement includes the labor of hundreds of men, women, and children who sustained Jesuit plantations, missions, and schools. Their forced labor culminated in the 1838 sale of 272 individuals from Maryland to Louisiana, one of the largest church-led sales of enslaved people in U.S. history. Today, descendants and researchers continue to trace family connections, preserve ancestral memory, and confront the legacy of Jesuit slaveholding.

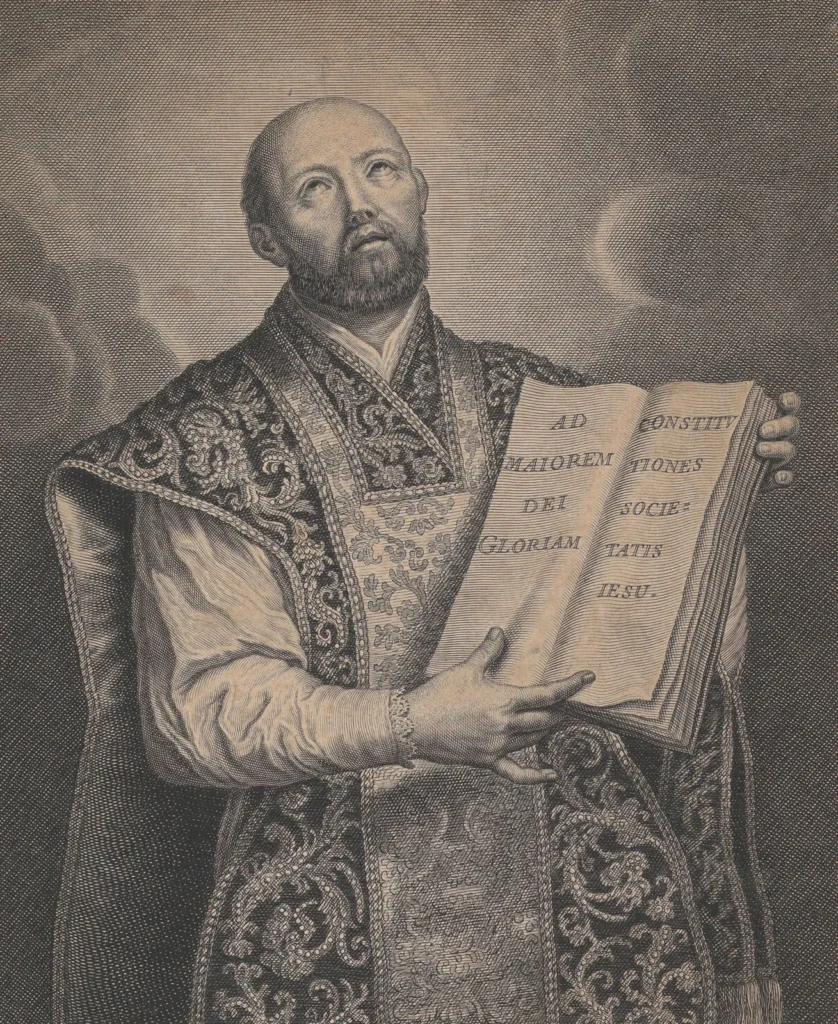

Who Were the Jesuits?

The Society of Jesus (Jesuits) is a Catholic religious order founded in 1540. While celebrated for its global missionary work and educational institutions, the Jesuits also financed their activities through enslaved labor on plantations.

- ➡️ Jesuit plantations in Maryland, including St. Inigoes, Newtown Manor, and St. Thomas Manor, were worked by enslaved people cultivating tobacco, wheat, and other crops.

- ➡️ Jesuits kept meticulous records, such as baptismal, marriage, and burial registers, which sometimes preserved rare details about enslaved families.

- ➡️ Income from these plantations supported Catholic missions and schools, including the founding of Georgetown College (now Georgetown University).

The 1838 Sale of 272 Enslaved People

By the 1830s, the Maryland Jesuits faced financial decline from falling tobacco yields and plantation mismanagement. In 1838, to secure their debts and fund their future, they sold 272 enslaved men, women, and children.

➡️ Families were forcibly separated, transported from Maryland to Louisiana, and placed in the brutal world of sugar plantations.

- ➡️ Jesse Batey – Purchased approx. 64 individuals, transported them to West Oak Plantation, Iberville Parish, Louisiana.

- ➡️ Henry Johnson – Purchased approx. 108 individuals, sending them to plantations in Ascension and Terrebonne Parishes, Louisiana.

Although the sale agreement stipulated that enslaved people remain Catholic and be treated humanely, these conditions were almost entirely ignored.

Maryland Plantations

- St. Mary's County | Charles County | Prince George County

- ➡️ Jesuits kept meticulous records, such as baptismal, marriage, and burial registers, which sometimes preserved rare details about enslaved families.

- ➡️ Income from these plantations supported Catholic missions and schools, including the founding of Georgetown College (now Georgetown University).

- Newtown | St. Inigoes | St. Thomas | White Marsh

| Plantation Name | Location | Approx. Number of Enslaved People | Notes |

| St. Inigoes Manor | St. Mary’s County | ~80-100 | This plantation often had one of the largest enslaved populations due to its size and output. |

| St. Thomas Manor | Port Tobacco, Charles | ~70-90 | Another large estate, serving as a central hub for Jesuit activities. Many sold to Louisiana buyers. |

| Newton Manor | Leonardtown, St. Mary’s | ~50-70 | Known for its agricultural activities and connections to Jesuit missions. |

| White Marsh Manor | Bowie, Prince George’s | ~40-60 | Records indicate it was smaller than some others but still significant in operations. |

| Bohemia Manor | Warwick, Cecil County | ~30-50 | Located on the Eastern Shore, this plantation was less populous but vital to Jesuit outreach in the region. |

| St. Joseph’s | Queenstown, Talbot County | ~20-40 | The smallest plantation, supporting Eastern Shore missions. |

The Fate and Destinations of the 272

When the Maryland Jesuits sold 272 enslaved men, women, and children in 1838, the majority were forced southward to Louisiana. Life on the sugar plantations of Iberville, Ascension, and Terrebonne Parishes was far more brutal than the tobacco farms of Maryland.

Enslaved families endured:

- ➡️ Long hours from sunrise to sunset during the sugar harvest

- ➡️ Dangerous boiling houses with scalding steam and heavy machinery

- ➡️ High mortality rates from exhaustion, heat, and poor nutrition

- ➡️ Family separations as spouses and children were sold apart

The Louisiana Buyers

The largest groups of Jesuit-enslaved individuals sold in 1838 were purchased by two Louisiana men: Henry Johnson and Jesse Batey. Together, they transported more than 170 men, women, and children from Maryland to Louisiana’s sugar plantations, where conditions were far harsher than the tobacco fields of the Chesapeake. The fate of the remaining individuals varied, with some sold to other buyers in Louisiana or left in Maryland for a few more years before being sold later.

Henry Johnson - Bill of Sales

Henry Johnson was a former U.S. congressman and governor of Louisiana. Approximately 108 individuals purchased (WikiTree Profile)

Johnson sent the enslaved people to his plantations in Ascension Parish and Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana. Like Batey, Johnson used these individuals primarily for work on his sugar plantations, which were a cornerstone of Louisiana’s economy.

➡️ Bill of sale for 56 persons from Thomas Mulledy to Henry Johnson, November 10, 1838

➡️ Bill of sale for 84 persons from Thomas Mulledy to Henry Johnson, November 29, 1838

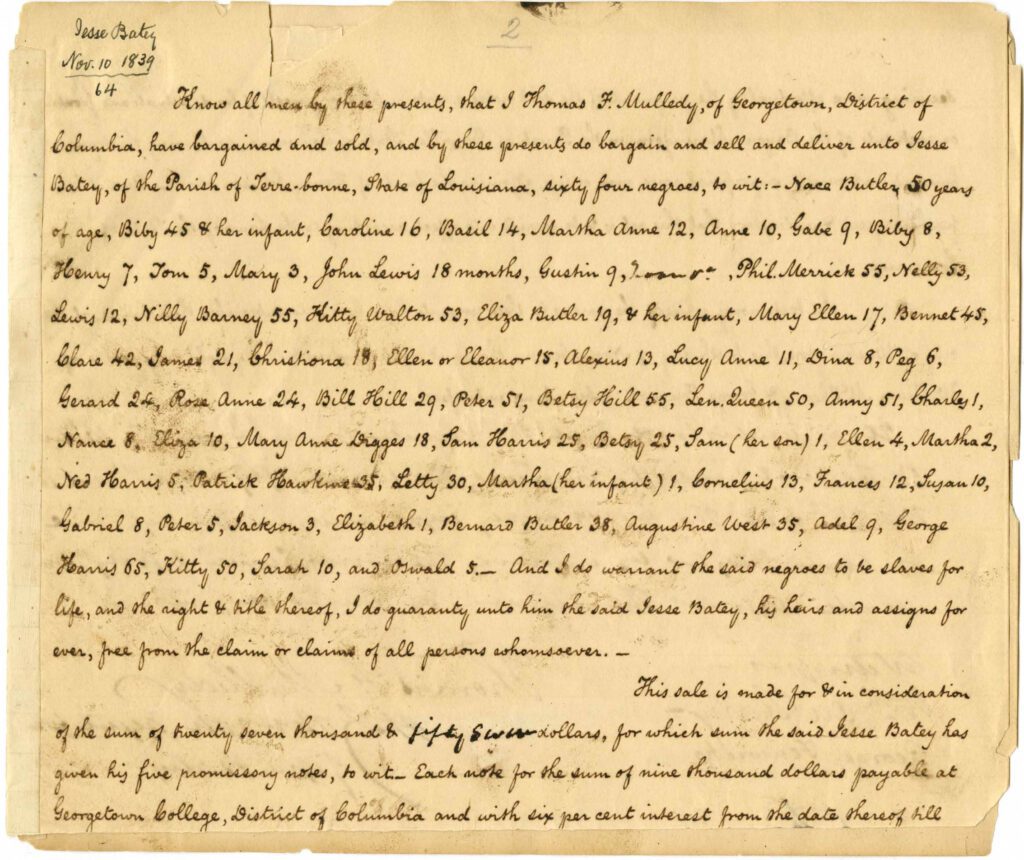

Jesse Batey - Bill of Sales

Jesse Batey, a wealthy sugar plantation owner. Approximately 64 individuals purchased. (WikiTree Profile)

Batey transported these individuals to his sugar plantation in Iberville Parish, Louisiana, near Maringouin. Their labor for sugar production is one of the most grueling types of plantation work.

Bill of sale for 64 persons from Thomas Mulledy to Jesse Batey, November 10, 1839 [1838]

“The individuals purchased by Johnson and Batey were taken to plantations in three parishes: Iberville, Ascension, and Terrebonne. The map below shows these Louisiana destinations.”

- West Oak (Iberville Parish) | Ascension Parish (Donaldsonville) & Terrebonne Parish (Houma)

- West Oak (Batey) | Ascension Parish & Terrebonne Parish (Johnson)

Jesuits After the 1838 Sale

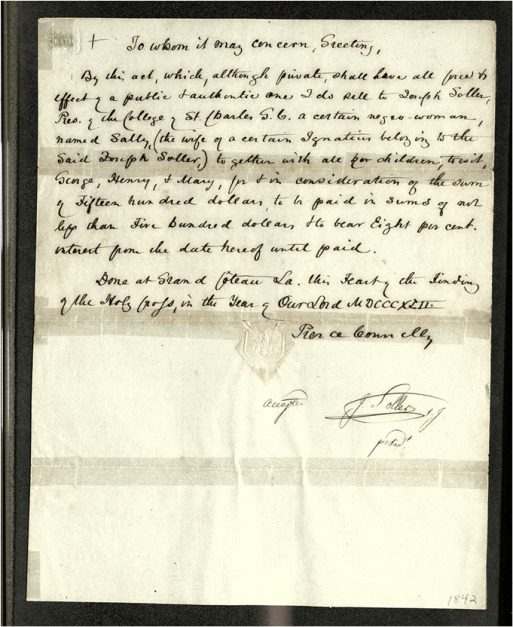

The 1838 sale did not end Jesuit slaveholding. For decades afterward, Jesuit priests in Maryland continued to hold enslaved people, sell them in smaller groups, and use their labor to sustain missions and schools. The document below, dated 1842, is a stark reminder of how enslaved men, women, and children were still treated as financial assets long after the 272 had been sold.

Archival evidence showing continued Jesuit involvement in slavery after 1838.

Researching & Certifying Jesuit-Enslaved Ancestry

Tracing ancestry connected to Jesuit enslavement often requires combining family memory, historical records, and modern tools such as DNA testing. To help descendants and researchers begin this journey, the GU272 Descendants Association has created a series of short educational videos. These resources explain the steps of becoming a certified descendant, introduce the role of DNA and genetic genealogy, highlight when to seek professional assistance, and provide guidance on building a family tree.

Organizations & Research Tools

These organizations and archives are leading efforts to document Jesuit enslavement, preserve family connections, and support descendant communities.

| Founded 2017 | |

| Primary Focus | Researching and preserving the genealogies and histories of descendants of individuals enslaved by Jesuits. |

| Relationship to Georgetown | Independent organization, may collaborate with Georgetown and other institutions for research. |

| Leadership | Led by genealogists, historians, and descendant members. |

| Approach | Research, historical documentation, and public education. |

| Goals | To document and share the stories of descendants and their enslaved ancestors. |

| For more information on the Descendants of Jesuit Enslavement Historical & Genealogical Society please visit our site | |

| Founded 2021 | |

| Primary Focus | Healing the wounds of slavery through truth, racial healing, and transformation. |

| Relationship to Georgetown | A partnership between Georgetown, the Jesuit Conference, and descendant communities. |

| Leadership | Co-chaired by descendant leaders and Jesuit representatives. |

| Approach | Collaboration, reconciliation efforts, and transformative initiatives. |

| Goals | To dismantle the enduring legacies of slavery and promote racial healing. |

| For more information on the Descendants Truth & Reconciliation Foundation please visit our site | |

| Founded 2015 | |

| Primary Focus | Genealogical research and historical documentation |

| Relationship to Georgetown | Independent of Georgetown University |

| Leadership | Run by independent researchers and genealogists |

| Approach | Research-driven |

| Goals | Preserve and document history |

| For more information on the Georgetown Memory Project please visit our site | |

| Founded 2015 | |

| Primary Focus | Reflecting on Georgetown’s historical ties to slavery and recommending steps for reconciliation. |

| Relationship to Georgetown | Internal Georgetown group, tasked with addressing its historical role in slavery. |

| Leadership | Composed of Georgetown faculty, students, and administrators. |

| Approach | Institutional reflection, research, and policy recommendations. |

| Goals | To acknowledge and address Georgetown’s involvement in slavery and its legacies. |

| For more information on the Georgetown University's Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation please visit our site | |

| Founded 2016 | |

| Primary Focus | Advocacy for reparative justice and community-building among descendants of the 272 enslaved people. |

| Relationship to Georgetown | Independent organization, collaborates with Georgetown on issues involving descendants. |

| Leadership | Led by descendants of the 272 enslaved individuals. |

| Approach | Advocacy, public awareness, and descendant-focused initiatives. |

| Goals | To preserve the memory of the enslaved, restore their honor, and seek reparative justice. |

| WikiTree - Georgetown GU272 | |

| For more information on the GU272 Memory Project please visit our site | |

| Founded 2016 | |

| Primary Focus | Research and educational collaborations on the legacy of slavery and its impact on descendants. |

| Relationship to Georgetown | Formal academic partnership between Southern University and Georgetown University. |

| Leadership | Jointly led by representatives from both institutions. |

| Approach | Academic collaboration, research, and public engagement. |

| Goals | To advance education, research, and dialogue on the history and legacies of slavery. |

Special Acknowledgment

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to David Patterson and Shannon Christmas for their invaluable contributions of materials, documentation, and research, which have greatly enriched the content of the Jesuit Enslavement page. Your dedication and expertise are deeply appreciated and instrumental in preserving this important history.

In Remembrance

May the lives of the Jesuit-enslaved and their descendants never be forgotten.