Preserving the Memory of Old Pine Hill Cemetery – Claiborne Parish, Louisiana

The Memorial Reads:

Old Pinehill Cemetery – Formerly Adkins Slave Cemetery

Claiborne Parish Louisiana 1850s – 1920s

The land originally purchased by Piety P. Sansing – Adkins was used as a burial ground for the enslaved.

Professor Lyle Gibson, Fulbright Scholar, historian, genealogist and documentary filmmaker has worked in higher education for more than 25 years, and has been involved in genealogy for over 33 years.

Old Pine Hill Slave Cemetery: Claiborne Parish, Louisiana

The Old Pinehill Cemetery, located a few miles south of Haynesville, Louisiana, in rural Claiborne Parish, stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of slavery and freedom. The cemetery sits on approximately one acre of land overgrown by pine trees and the passing of time. The history of the cemetery is but a microcosm of the history of Claiborne Parish, Louisiana. During the 1850s, many settlers, including slaveholders, left parts of the Southeast to migrate west to Texas in search of available land and economic opportunities. For members of the Adkins family, migration westward was an opportunity for something new.

Migration of the Adkins Family

The matriarch of the family, Piety Prudence Sansing-Adkins, became a widow in 1827 upon the death of her husband, Zacheus Adkins, in Henry County, Georgia. Left to raise her young children alone, Piety embodied resilience and determination. By 1852, she joined the great westward migration, leaving Georgia with her children and a group of enslaved people, relocating first to Louisiana and later to Texas.

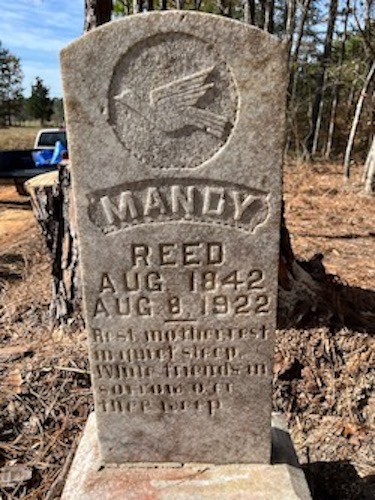

Mariah and Her Children

Among those enslaved who traveled with Piety was Mariah, an African American woman whose family exemplifies the hidden genealogies preserved through oral history and archival records. Mariah’s children included:

- ➡️ Elbert (b. c. 1830)

- ➡️ Joe (b. c. 1832)

- ➡️ Sam (b. c. 1834)

- ➡️ Irene (b. c. 1836)

- ➡️ Andrew (b. c. 1838)

- ➡️ Winny (b. c. 1841), who may later have appeared in postbellum records as Sarah W. Davis, wife of Alfred Davis.

This possible identification of Winny as Sarah W. Davis represents an important genealogical bridge, connecting antebellum lives to postbellum African American family networks in Claiborne Parish and beyond.

The Westward Journey and Settlement in Claiborne Parish

The Adkins family, accompanied by Mariah and her children, set out around 1852 on a journey by horse- and ox-drawn wagons bound for Texas. Their migration westward reflected the broader mid-nineteenth century movement of settlers seeking opportunity and land on the expanding frontier.

Family oral tradition, passed down through Mariah’s son Elijah, recalls that during this journey, the wagon broke down in Claiborne Parish, Louisiana. This event proved pivotal. Instead of continuing on to Texas, the family decided to remain in Claiborne Parish, where they would establish lasting roots. Elijah conveyed stories of the journey to his children and grandchildren, ensuring that the memory of this moment was preserved across generations.

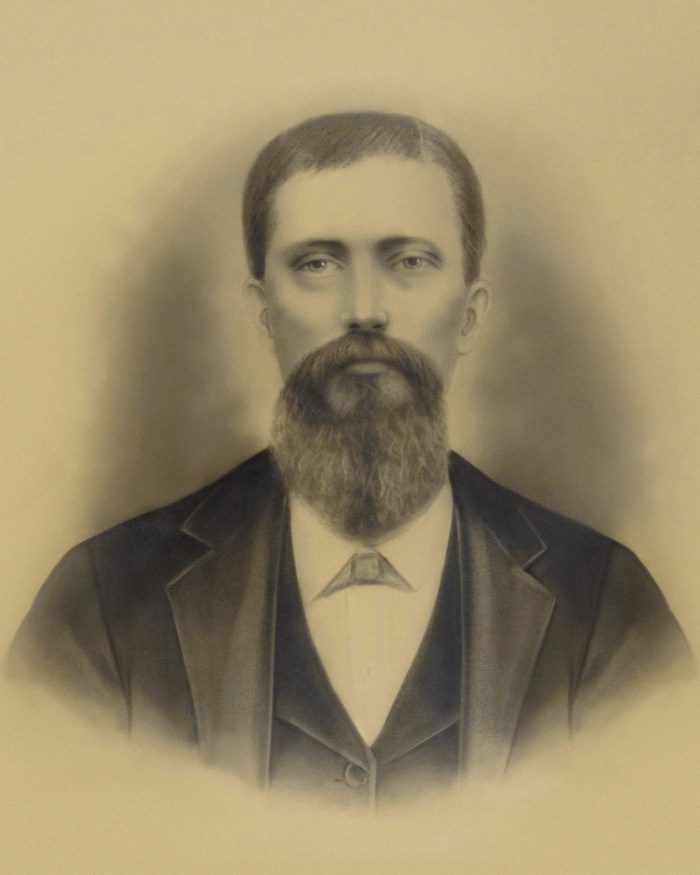

Children of Mariah and Lemiah Christopher Columbus Adkins

The record of enslavement also bears the mark of exploitation and violation. Four of Mariah’s younger children were fathered by Lemiah Christopher Columbus Adkins, son of Piety Adkins. These children included:

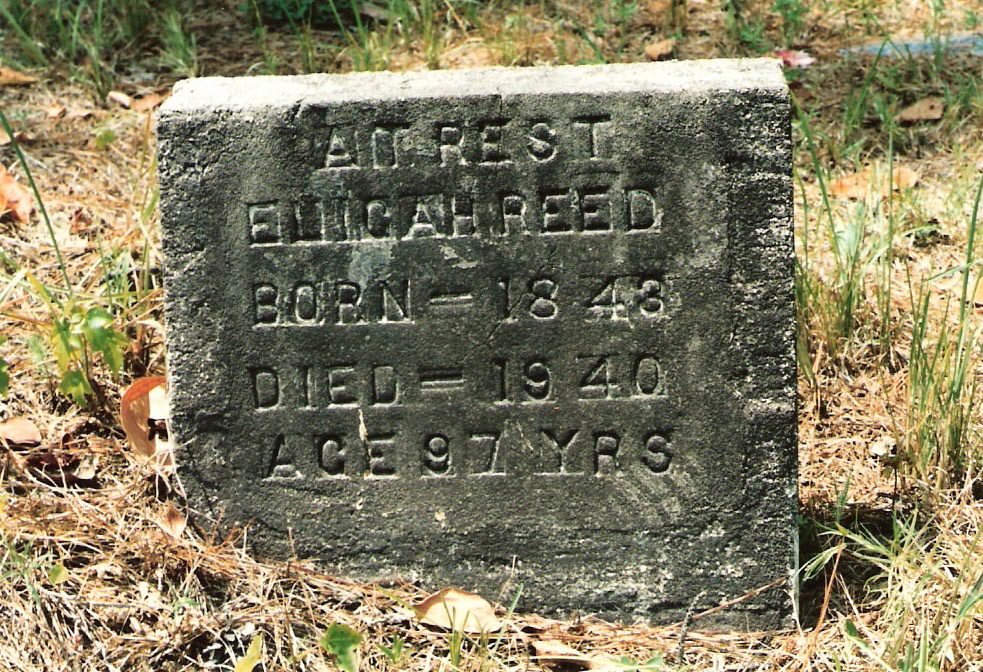

- ➡️ Elijah Adkins Reed 1843-1940

- ➡️ Mary Adkins-Biddle (b. 1850)

- ➡️ Dock Ellis (b. 1852)

- ➡️ Dorcas (b. c. 1854)

This intertwined lineage demonstrates the dual legacy of Old Pinehill Cemetery: a resting place for both the enslaved and their enslavers. For descendants today, these names provide a roadmap for reconstructing family histories across divides of race, freedom, and bondage. They also highlight how African American genealogical research often requires tracing enslavers’ family histories in parallel with those of the enslaved.

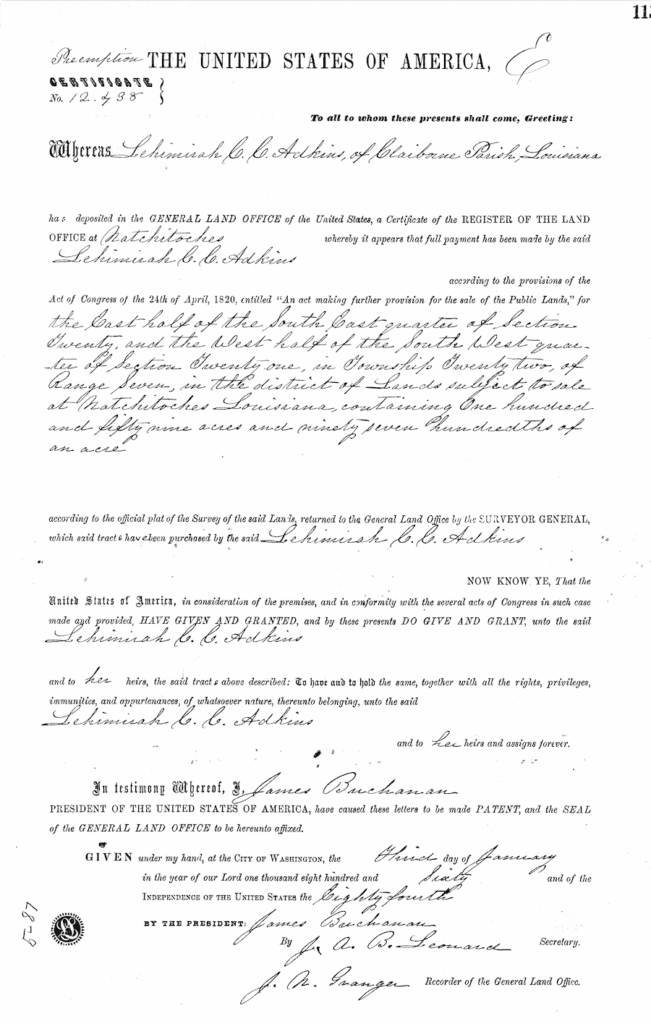

Land Acquisition

Between 1855 and 1859, Piety Prudence Sansing-Adkins and her son, Lemiah Christopher Columbus (LCC) Adkins, purchased government land in Claiborne Parish. The acquisition of this property not only signaled their permanent settlement in the region but also intertwined their family’s legacy with that of the local community.

Remarkably, much of this land remains in the hands of Adkins’ descendants today, a living reminder of decisions made during that mid-nineteenth-century migration. For descendants of Mariah’s family, this land and cemetery represent both bondage and resilience, spaces where histories of enslavement and survival converge.

Transition from Old Pinehill to New Pine Hill Cemetery

By the 1920s and 1930s, burials in Old Pinehill Cemetery had ceased, for reasons that remain uncertain. Whether due to overcrowding, difficulty accessing the site, or cultural changes in burial practices, the one-acre cemetery fell into disuse. The passing of time and encroaching pine trees gradually concealed many of its graves, leaving only oral history and scattered markers to testify to the lives of those interred there.

The Old Pine Hill Slave/African American Cemetery holds immense historical significance, serving as a testament to the lives and struggles of those who were enslaved and those interred during the Reconstruction, Post-Bellum and early twentieth century. Its preservation not only honors the memory of those buried but also fosters a deeper understanding of the area’s past, allowing the community to acknowledge and learn from this vital part of its history while promoting respect and awareness for future generations.

In 1940, a new chapter began with the establishment of the New Pine Hill Cemetery. The land was generously donated by Frank Reed, son of Elijah Adkins Reed, ensuring that the community’s burial traditions could continue in a dignified and sustainable way.

New Pine Hill Cemetery

The first documented burial at New Pine Hill Cemetery was that of Elijah Adkins Reed himself, who was interred there in April 1940. His burial marked both an end and a beginning: the closing of Old Pinehill’s role as a community resting place and the founding of a new cemetery that would serve descendants and neighbors for generations to come.