Compensated Emancipation

During and after the Civil War, the transition from slavery to freedom was documented through two powerful federal mechanisms: Compensated Emancipation and the Index of Slave Compensation Claims. Both are deeply connected to the lives of the United States Colored Troops (USCT).

In 1862, the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act became the first federal law to free enslaved people by paying loyal slaveholders for their “loss of property.” The act not only recorded enslavers’ names but also created rare lists of freed individuals—many of whom later served in the USCT.

In the border states of Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, Tennessee, and West Virginia, slavery remained legal during the war. When enslaved men from these states enlisted in the Union Army, their enslavers submitted claims to the federal government for financial reimbursement. These claims often included the name of the soldier, his regiment, and details about the enslaver, forming a critical paper trail that links military service to the institution of slavery.

Compensated emancipation was a government-funded process that paid slave owners $300 for each enslaved individual who enlisted, provided the enslaver could prove loyalty to the Union. This sum, while significant, was generally lower than the market value enslavers assigned to human beings, underscoring both the injustice of slavery and the limitations of emancipation policies.

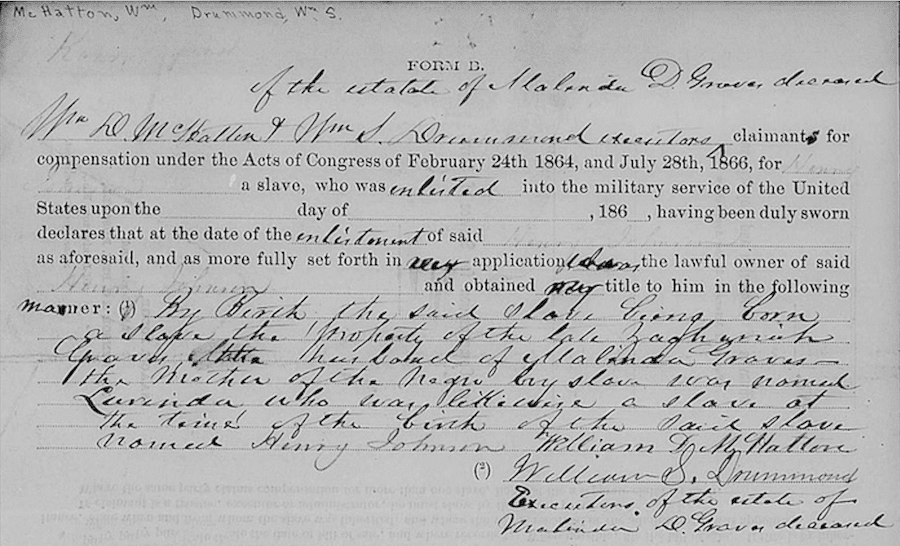

Sample of Compensated Emancipation Records

Form B

of the estate of Malinda D. Grave deceased

William D. McHatton and William S. Drummond executor’s claimant for compensation under the Act of Congress of February 24th 1864, and July 28th, 1866, for Henry Johnson a slave, who was enlisted into the military service of the United States upon the __ of ____, 186_, having been duly sworn declares that at the date of enlistment of the said Henry Johnson as aforesaid, and as more fully set forth in my application whereas the lawful owner of the said Henry Johnson and obtained my title to him in the following manner:

(1) By Birth the said slave being born a slave the property of the late Zachariah Graves, the late husband of Malinda Graves, the Mother of Negro boy slave was named Lurinda who was likewise a slave at the time of birth of the said slave named Henry Johnson.

William D. McHatton,

William S. Drummond

Executors of the estate of

Malinda D. Graves deceased

What's the Key Points of these records?

Enslaved men who joined the Union Army often became part of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Since they were property by law in slaveholding states, their enlistment could be considered a "taking" by the government, prompting the government to create compensation measures.

To receive compensation, slave owners had to prove loyalty to the Union and submit a claim documenting the enlistment of the enslaved person.

Compensation claims were typically filed with the War Department or other designated agencies.

In the slave compensation claims system during the Civil War, the maximum amount that a slave owner could claim for an enslaved individual who enlisted in the Union Army was $300 per person. This amount was standardized and applied regardless of the enslaved person’s age, skills, or background. This amount was often lower than the enslaved person's market value.

Here’s how this maximum compensation amount worked in practice:

1) Flat Rate Per Enlisted Individual: The federal government determined a fixed compensation rate of $300 per enslaved person who enlisted. This amount aimed to compensate loyal Union slave owners for the "loss of labor" without delving into variable valuations.

This flat rate did not account for the actual "market value" that slave owners may have placed on individuals, which could be much higher.

2) No Additional Compensation for Death or Injury: The $300 was the maximum compensation regardless of the outcome of the enlistment. If an enslaved individual died in service or was injured, no additional compensation was awarded to the owner.

3) Limitations on Multiple Claims: Owners could file multiple claims if several enslaved people from their holdings enlisted, with $300 paid per person enlisted. However, each claim had to meet specific eligibility criteria, such as the owner’s loyalty to the Union.

4) Purpose and Policy: The $300 was a way for the Union government to incentivize slave owners to allow enslaved individuals to enlist without significant financial "loss." However, many owners considered it insufficient, as it often didn’t reflect the enslaved person’s market value.

While the amount might seem minimal compared to the actual value that enslaved individuals represented to slave owners, it provided a fixed, manageable compensation policy aligned with the Union's military and political goals.

1) Military Enlistment: Compensation was primarily issued to slave owners if the enslaved individual enlisted in the Union Army, typically joining the United States Colored Troops (USCT).

2) Loyalty of Slave Owner: Only slave owners who were loyal to the Union could file for compensation. Confederate supporters were excluded, limiting the program to Union-aligned owners.

3) Freedom of the Enslaved Individual: In some compensated emancipation programs, such as Washington, D.C.’s in 1862, enslaved people did not have to enlist but were freed with compensation given to their owners.

4) Responsibilities of Enslaved Individuals: Enslaved individuals who enlisted were expected to serve in the Union Army, typically for the remainder of the Civil War. They were assigned various duties, including combat, labor, and support roles, depending on the needs of the regiment.

The enlistment meant the enslaved individual would be required to complete their service and follow the duties typical of Union soldiers, receiving military training, equipment, and provisions.

5) Age Range for Enslaved Individuals: Generally, young adult men, especially those between ages 18 and 45, were targeted for enlistment. This age range aligned with the standard enlistment guidelines of the time, emphasizing those physically able to serve.

In some cases, boys as young as 16 were accepted, though this varied depending on regional military needs and the discretion of recruiting officers.

Older enslaved men and women, as well as young children, were not eligible for compensation related to enlistment unless they were emancipated under different compensated emancipation policies, such as those enacted in Washington, D.C., where no specific age limits were mandated.

If an enslaved soldier died in service, the owner was still eligible to receive the $300 compensation. The payment served as a flat fee for the "loss" rather than a reflection of any specific contribution to the war effort or the soldier's fate.

1) Failure to Prove Loyalty to the Union: Only Union-loyal slave owners were eligible for compensation. If a claimant could not prove loyalty or had supported the Confederacy, the claim would be rejected. This was a key requirement, especially in border states with divided loyalties.

2) Inadequate Documentation of Ownership: Claimants had to provide documentation proving ownership of the enslaved individual. If they lacked legal proof, such as bills of sale or estate records, the claim would likely be denied.

3) Failure to Prove Enlistment: The claim had to show that the enslaved person actually enlisted in the Union Army. If there was no record of enlistment or if the government could not confirm it, the claim would be dismissed.

4) Claims Filed Outside of Approved Areas or States: The federal government restricted compensation claims to certain regions, particularly in border states where slavery was legal, yet owners remained loyal to the Union. Claims filed outside these states were not eligible.

5) Disputes Over Compensation Amounts: Some claims were rejected if there was a dispute over the amount of compensation. If a claimant argued for a higher valuation than the standard $300, the claim could be denied or delayed.

6) Fraudulent Claims or Inconsistencies: In cases of fraud or suspected deception—such as inflated claims of ownership or enlistment—claims were carefully scrutinized and often rejected if inconsistencies were found.

7) Late Submission of Claims: Claims had to be filed within a specific time frame. Any claims submitted after the deadline were typically rejected, as the government sought to close the program and settle all valid claims promptly.

8) Incorrect Filing Procedures: If the claim was filed improperly, such as through the wrong department or lacking required forms, it could be rejected. Some claimants were unfamiliar with the procedures, leading to disqualification due to technicalities.

9) Legal Disputes Over Enslaved Individuals’ Status: Some enslaved people had ambiguities around their status, such as partial manumission or conflicting claims to ownership. Legal disputes over these issues could result in the rejection of claims.

10) Claims from Owners of Enslaved Individuals Who Deserted or Were Freed Elsewhere: If an enslaved individual deserted the military, escaped before enlisting, or was freed in another jurisdiction, the owner would have no valid claim, and any submission for compensation would be denied.

These records typically document the enlistment of the individual into the United States Colored Troops (USCT), including the regiment or company, dates of service, and sometimes information on death or discharge.

Enlistment records within the USCT can provide information on enlistment dates, physical descriptions, and sometimes pension records, which are rich with personal details.

If an enlisted enslaved person survived the war, they might later qualify for a military pension. Pension files can include personal testimonies, affidavits from family members, and information about marriages and children, offering further biographical insights.

Understanding the Compensation Rates

Understanding the compensation rates helps reveal both the economic logic used by the federal government and the human cost behind these records. While enslavers received fixed sums for the loss of enslaved labor, the payments rarely matched the market values they claimed, exposing the unequal nature of compensated emancipation. The table below highlights the differences in compensation amounts and why these records remain such a critical resource for genealogists.

| Category | Compensation Amount | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Enslaved person who enlisted in Union service | $300 | Required proof of Union loyalty and legal ownership by the enslaver |

| Enslaved person who was drafted | $100 | Lower compensation, reflecting involuntary service |

| Average market value claimed by enslavers | $500–$1,200 | Highlights the disparity between government payments and enslavers’ own valuations |

Timeline of Compensated Emancipation

and Related Records

April 16, 1862

District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act passes, freeing ~3,100 enslaved individuals and compensating loyal slaveholders.

1862

1863–1865

USCT enlistments rise across border states; enslavers begin filing claims.

1863–1865

1866–1867

Missouri and other border states file compensation claims under federal law.

1866–1867

1871–1880

Southern Claims Commission processes petitions from Union loyalists for wartime property losses (not exclusively slavery-related, but closely linked to compensation records).

1871–1880

Locating Compensated Emancipation Records

While the Missouri collection is the largest, other border states, Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Tennessee, and West Virginia, also filed claims during and after the war. Researchers will find these collections especially valuable for tracing enslaved ancestors who transitioned into service as U.S. Colored Troops.

📦 Research on Ancestry

Ancestry provides digitized compensation petitions from Washington, D.C. (1862–1863) and Missouri (1866–1867). These records name enslaved people, their enslavers, and often the regiments where freed men served in the USCT.

📦 Research on FamilySearch

FamilySearch provides free access to Slave Compensation Records (1866–1867), filmed from the National Archives. These records document enslaved men and their enslavers, making them an important source for genealogists tracing African American families.

📦 Research on Fold3

Fold3 features military-related records, including the District of Columbia Slave Owner Petitions (1862). It also offers the Southern Claims Commission Approved Claims (1871–1880), documenting property losses by loyal Unionists, some tied to emancipation.

📦 Research at NARA

The National Archives preserves the original petitions, payment registers, and treasury accounts of compensated emancipation. While some files are digitized, the most complete documentation is available onsite or via microfilm research. RG 217

📄 Download the Index of Slave Compensation Claims by Former Slave Owner (PDF)

This index provides the names of enslaved men, their enslavers, and the states where claims were filed between 1864 and 1867. Drawn from National Archives microfilm (RG 217, Treasury Department, T1131), it serves as a guide to petitions in Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Virginia, and West Virginia. Researchers can use it to locate original compensation records and connect military service to the institution of slavery.