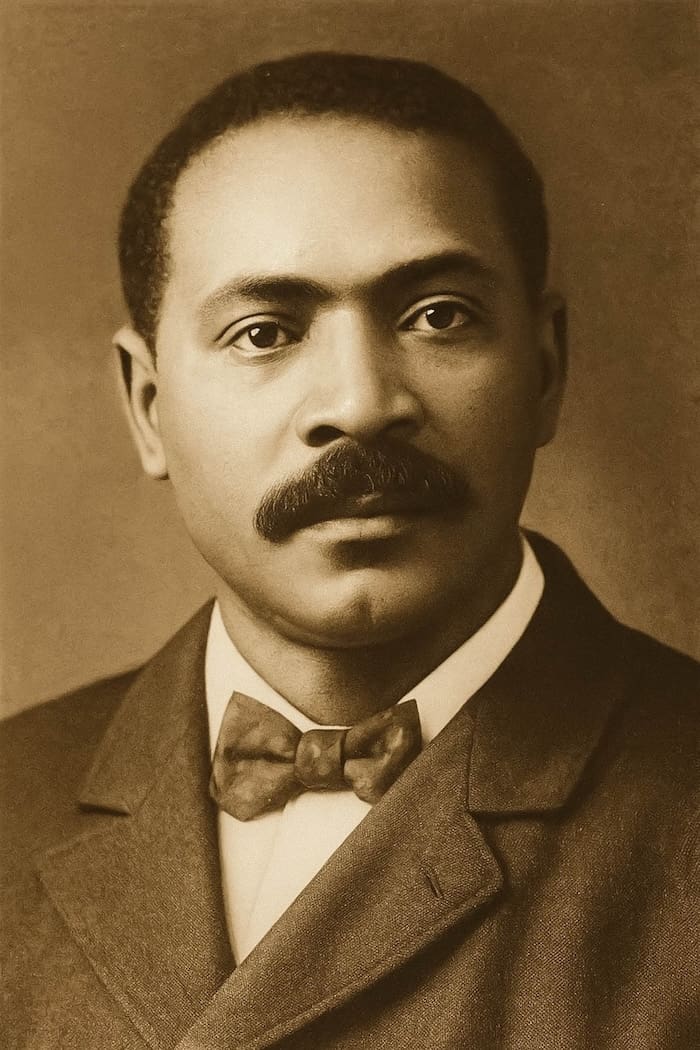

Isaiah’s position as a land agent for the Louisville, New Orleans, and Texas Railroad gave him the strategic leverage to place Mound Bayou along vital rail lines, ensuring both accessibility and economic opportunity. The earliest settlers — many formerly enslaved families from Davis Bend — faced the monumental task of transforming dense swamp into livable land. Despite disease, hardship, and inhospitable conditions, they persevered, building what would become one of the most enduring symbols of Black independence in American history.

Honoring the Legacy of Mound Bayou, Mississippi

- HM

- Marlin, Texas

- Rev. Dr. John Mendez

Mound Bayou is more than a town, it is a living symbol of Black resilience and leadership. From Davis Bend to the Delta, its people built a home where freedom and self-determination could thrive. This memorial honors its founders, its history, and the community leaders who carry that legacy forward today.

The Story of Davis Bend and Mound Bayou

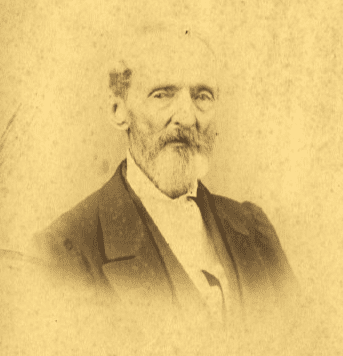

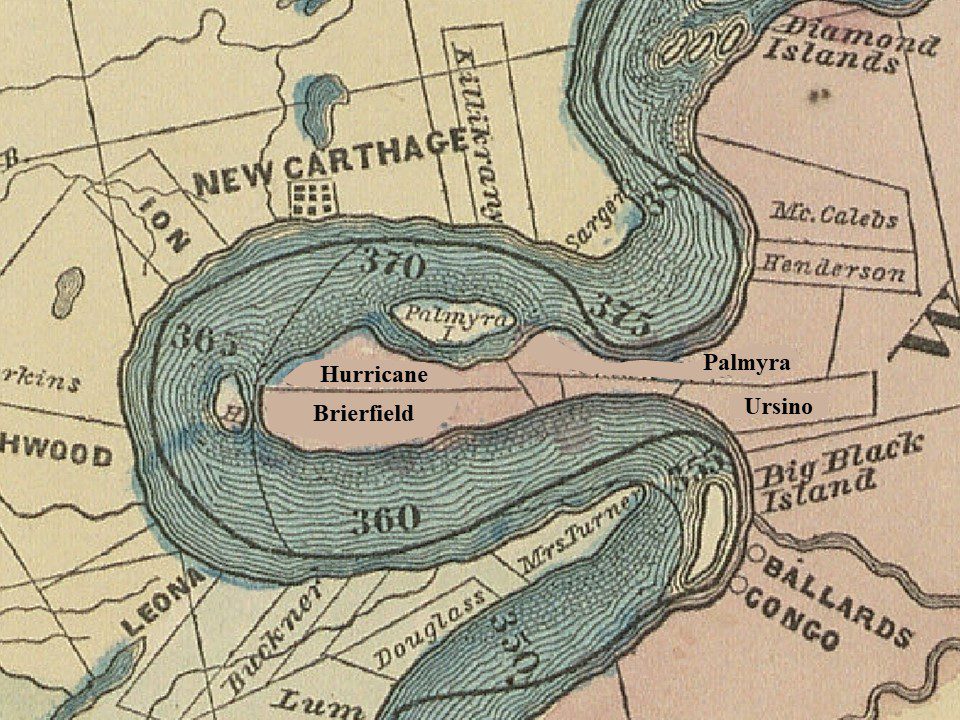

The origins of Mound Bayou begin with Davis Bend, a cotton plantation community in Mississippi owned by Joseph Davis, the older brother of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Unlike most enslavers, Joseph Davis allowed a measure of self-governance among the enslaved, encouraging them to resolve disputes, manage work, and even run small businesses.

After the Civil War, formerly enslaved people from Davis Bend, including the Montgomery family, carried forward those lessons of self-governance, entrepreneurship, and community life. When Davis Bend declined under Reconstruction pressures, these families sought to create something new: a Black town entirely of their own.

Joseph Davis’ Experiment in Self-Governance

Joseph Davis, elder brother of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, managed his plantation at Davis Bend in a way that stood apart from most enslavers of his time. While still maintaining the institution of slavery, he experimented with granting certain responsibilities to the enslaved, allowing them to settle disputes, oversee work, and develop business skills. This unusual approach created space for leadership to emerge among men like Benjamin Montgomery, whose talents in management and enterprise became the foundation for a larger vision of Black self-governance.

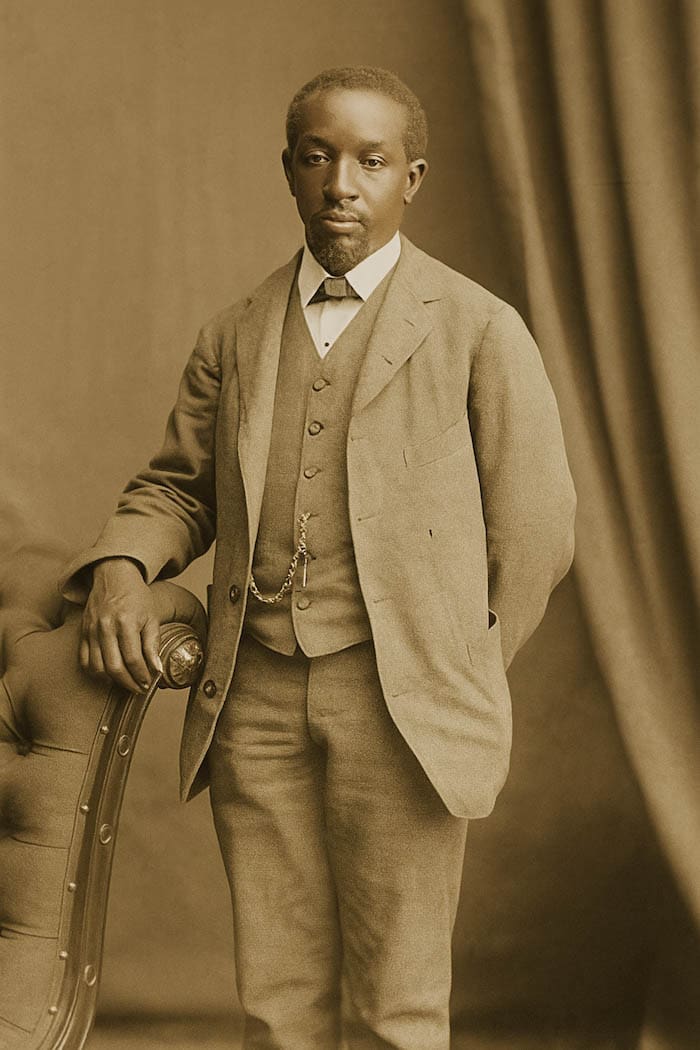

Benjamin Montgomery & the Rise and Fall of Davis Bend

In 1866, Joseph Davis sold Davis Bend to Benjamin Montgomery for $300,000 (nearly $5 million today). Montgomery became the first African American elected to public office in Mississippi and oversaw cotton so fine it was celebrated at international expositions in 1870.

But Davis Bend faced devastating floods and economic hardship. By 1876, Montgomery was forced into default and the land reverted to the Davis family. He died the following year — but his dream endured through his son Isaiah, who carried the vision forward.

Transition to Founders

Though Davis Bend eventually declined, its experiment in self-governance inspired a new chapter. In 1887, Isaiah T. Montgomery, son of Benjamin, and his cousin Benjamin T. Green secured 840 acres of untamed, mosquito-infested wilderness in Bolivar County, Mississippi. Determined to fulfill Benjamin Montgomery’s dream, they used savings, profits from earlier ventures, and support from Black mutual aid networks to establish Mound Bayou — not merely as a settlement for survival, but as a model of self-determined, Black-led prosperity.

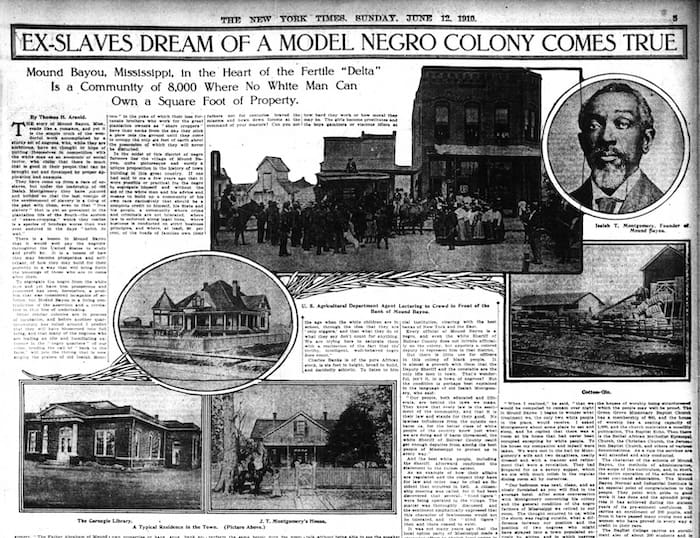

June 12, 1910

Ex-Slave Dream Of A Model Negro Colony Comes True

THE story of Mound Bayou, Miss., reads like a romance, and yet it is the simple truth of the wonderful work accomplished by a sturdy set of negroes, who, while they are ambitious, have no thought or hope of putting themselves in competition with the white man as an economic “Access fully transcribed article below.”

The Jewel of the Delta

By the early 20th century, Mound Bayou emerged as a thriving, majority-Black municipality, governed entirely by Black residents a radical achievement in Jim Crow-era Mississippi. The town featured:

- ➡️ Two sawmills and three cotton gins

- ➡️ A Carnegie Library and multiple schools

- ➡️ A bank and thriving Black-owned businesses

- ➡️ Newspapers, civic organizations, and churches

- ➡️ An Olympic-sized swimming pool and even a zoo

In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt, deeply impressed by the town’s self-sufficiency, declared Mound Bayou “an object lesson full of hope for the colored people.” For Black families across the Delta, Mound Bayou became a sanctuary—where they could own land, educate their children, walk the streets without fear, and build generational wealth beyond white interference.

Triumphs and Tragedy:

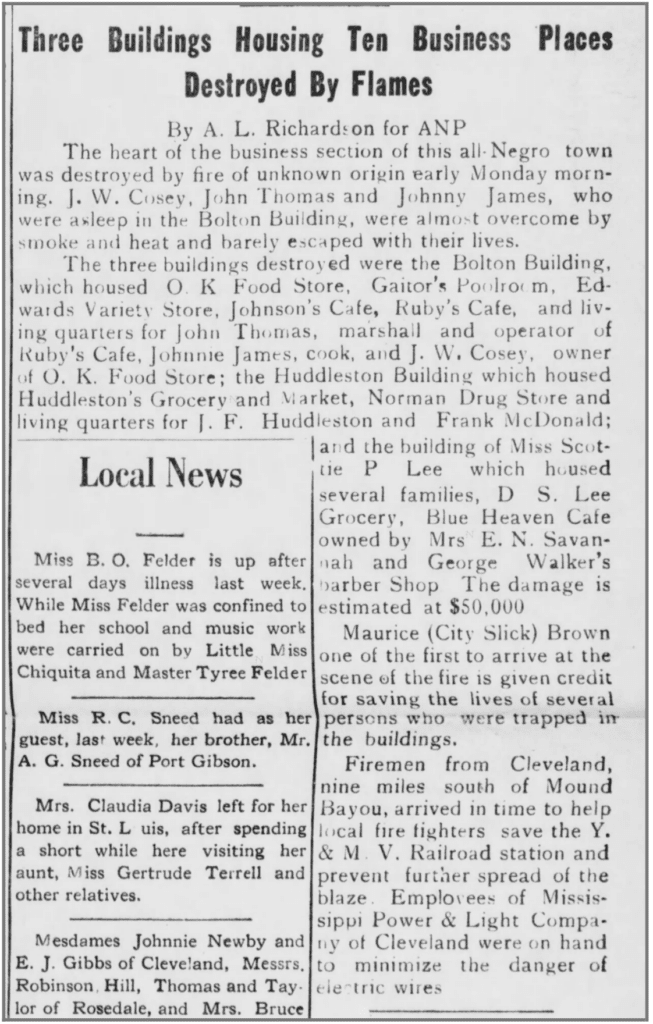

The Burning of Downtown Mound Bayou

Despite its remarkable self-sufficiency, Mound Bayou was not immune to tragedy. In 1941, a devastating fire swept through the town’s commercial district, reducing much of downtown Mound Bayou to ashes. The blaze destroyed numerous Black-owned businesses, offices, shops, and community spaces that had taken decades to build.

For a town founded on the principles of Black economic independence, the loss was more than physical it struck at the heart of what Mound Bayou represented: prosperity under Black leadership, achieved despite segregation and oppression.

Arson was widely suspected, though never conclusively proven, fueling suspicions that the fire may have been an act of racial sabotage designed to undermine one of the South’s most successful Black communities. Yet, true to their legacy of perseverance, the people of Mound Bayou rebuilt.

Community leaders, fraternal organizations, and residents rallied to restore essential services and revive the town’s economy.

The fire, though crippling, did not extinguish the vision of Black self-governance and communal resilience.

The downtown fire joined the long list of hardships faced by the people of Mound Bayou, including floods at Davis Bend, economic decline, and political suppression, all with unwavering determination. Rather than signaling defeat, each challenge reinforced Mound Bayou’s enduring lesson:

Black excellence, unity, and self-reliance are not easily erased—even by fire.

Click image to enlarge

Healthcare, Education, and Civil Rights

The pinnacle of Mound Bayou’s independence came with the opening of Taborian Hospital in 1942, built by the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor, a Black fraternal organization. The 42-bed, Art Deco facility was staffed entirely by Black physicians and nurses, most trained at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee.

Beyond its medical contributions, Mound Bayou played a quiet but critical role in the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement.

The town became home to Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a surgeon, entrepreneur, and activist who provided safe haven for witnesses in the infamous Emmett Till murder case. Dr. Howard also mentored future icons like Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer, both of whom were profoundly influenced by the town’s example of Black self-governance.

Mound Bayou: A Sanctuary from Racial Terror

While Mound Bayou is often remembered for its Black-owned businesses, pioneering institutions, and civic leadership, it was equally vital as a refuge, a literal safe haven for Black families escaping the brutality of the Jim Crow South.

In an era when lynchings, Klan violence, and white supremacist mobs terrorized communities across Mississippi, Mound Bayou stood as a protective fortress governed entirely by Black leaders. Here, African Americans fleeing racial violence could find temporary shelter, medical care, and a community determined to shield its own from the horrors just beyond its borders. Mound Bayou stood as a protective fortress governed entirely by Black leaders.

As oral histories and contemporary accounts reveal, families on the run from white mobs could disappear into Mound Bayou, find temporary shelter, regroup, and plan their next steps, shielded by the solidarity of an entire town committed to their defense.

Even during peak moments of racial terror, the Red Summer of 1919, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, or the backlash to Civil Rights organizing the streets of Mound Bayou offered a rare sense of security for African Americans otherwise living under siege.

Emmett Till’s Family and Mound Bayou’s Role

This sense of refuge became especially evident in the aftermath of the Emmett Till murder, one of the most notorious racial killings in American history.

In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till, a Black teenager from Chicago, was kidnapped, tortured, and brutally murdered while visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, after being falsely accused of whistling at a white woman. His mutilated body, recovered from the Tallahatchie River, shocked the nation and galvanized the Civil Rights Movement.

But what is less widely known is the role Mound Bayou played in offering protection to Emmett Till’s grieving mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, and others connected to the case. Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a prominent Mound Bayou resident, surgeon, and civil rights activist, transformed his home and network into a shield of safety for witnesses, journalists, and family members facing death threats from white mobs.

His leadership ensured that critical figures in the Till case, those willing to testify or speak publicly, could find protection within Mound Bayou’s self-governed, Black-led boundaries.

Mamie Till-Mobley, devastated but determined to seek justice for her son, found allies in Mound Bayou’s residents. The town’s reputation as a “safe haven” attracted those resisting racial terror, offering both physical protection and moral support during one of the most volatile chapters in Mississippi history.

A Legacy That Inspires

Mound Bayou is more than a historical footnote it remains a beacon of what Black communities can achieve with unity, vision, and self-determination. Notable figures with roots in Mound Bayou include:

- ➡️ Isaiah T. Montgomery – Founder, first mayor, national advocate for Black self-reliance

- ➡️ Dr. T. R. M. Howard – Surgeon, civil rights pioneer, protector of Emmett Till's family

- ➡️ Medgar and Myrlie Evers – Civil rights activists who drew inspiration from Mound Bayou

- ➡️ Fannie Lou Hamer – Voting rights icon, who spent her final days in Mound Bayou

- ➡️ Katie Hall – U.S. Representative from Indiana, born in the town

Modern Advocates of Mound Bayou, MS

Hermon Johnson Sr.

Mound Bayou, MS

Museum founder, Mound Bayou Museum of African American Culture & History

Hermon Johnson Sr.

Mound Bayou, MS

Custodian of living memory—his firsthand recollections preserve the town’s oral histories and early narratives

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com

Hermon Johnson Jr.

Mound Bayou, MS

Director of the Mound Bayou Museum of African American Culture & History

Hermon Johnson Jr.

Mound Bayou, MS

Oversees exhibitions on Emmett Till, Mamie Till-Mobley, and the town's founders; shapes digital storytelling and outreach via social media campaigns

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com

Darryl Johnson Sr

Mound Bayou, MS

Former Mayor; Co‑founding member of the Historic Black Towns & Settlements Alliance

Darryl Johnson Sr

Mound Bayou, MS

Advocates for state and federal recognition and funding; spearheads educational programs to ensure Mound Bayou’s narrative is included in school curricula

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com

Barbara Johnson

Mound Bayou, MS

(Hypothetical Young Leader)

Generates awareness and attracts wider interest in Mound Bayou; lauded by Hermon Johnson Jr. for her creative contributions

- Phone:+1 (234) 567=8910

- Email:info@example.com

Mayor Eulah Peterson

Mound Bayou, MS

Advocates for economic redevelopment and educational excellence; emphasized restoring the town’s spirit during her tenure

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com

Annyce Campbell

Mound Bayou, MS

Featured by Smithsonian’s Delta Jewels project; bridges generational wisdom and national recognition

- Phone:+1 (234) 567=8910

- Email:info@example.com

Will Jacks

Mound Bayou, MS

Supports the preservation of heritage markers and public history initiatives; highlights Mound Bayou in educational programming

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com

Haneefah Muhammad

Mound Bayou, MS

Revitalizes civic engagement through weekly storytelling and community updates

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com

Peter Woods

Mound Bayou, MS

Revived small-town commerce through artisanal pottery; helps draw visitors and preserves traditional crafts

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com

P.M. Smith

Mound Bayou, MS

P.M. Smith is recognized for spearheading preservation initiatives, supporting heritage tourism, and actively mentoring young leaders in Mound Bayou. Smith’s work focuses on connecting the town’s historical narrative to broader movements in Black heritage, ensuring that Mound Bayou’s story continues to inspire both local residents and national audiences. Through lectures, historical interpretation, and community outreach, P.M. Smith has become a vital voice in the modern revitalization of Mound Bayou.

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com

Rev. Earl Hall

Mound Bayou, MS

Promotes education and community development; passionate about maintaining local schools and reinforcing generational pride

- Phone:+1 (234) 567-8910

- Email:info@example.com